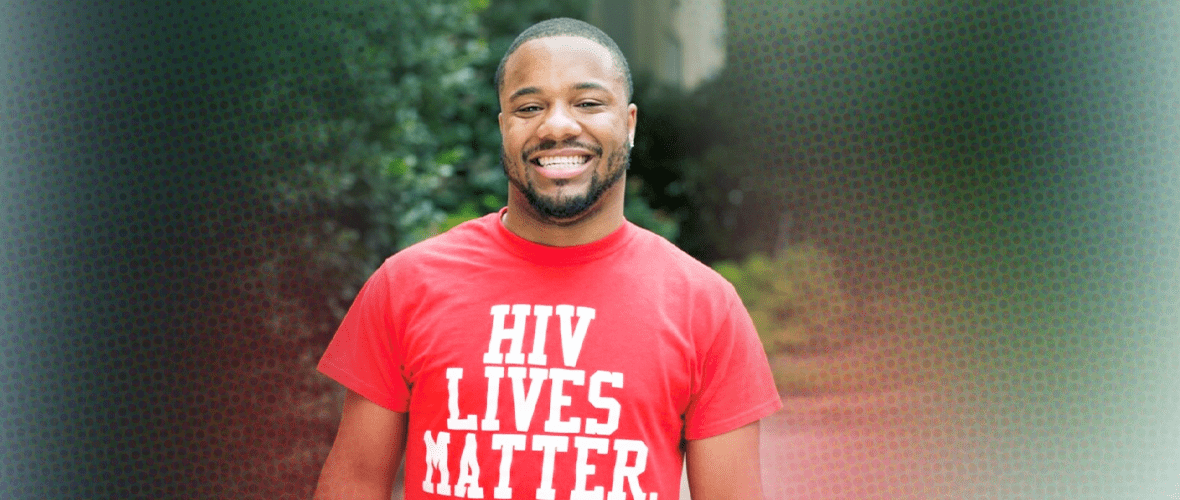

By Porchia Dees

I am a Beautiful Black Queen Living with HIV. It has taken a long time for me to come to terms with that statement because the concepts of beauty and HIV don’t usually go together. Growing up poz and trying to cope with the stigma surrounding my experience has been challenging, to say the least. I am a part of the first generation of children who were born positive. I was born on Dec. 5, 1986. At the time, my biological mother was using drugs and heavy in her addiction. If it weren’t for my aunt, who I call mom and who took legal guardianship of me, I don’t think I would be here today.

My pediatrician told my parents that he didn’t think I’d live to see my 5th birthday, but clearly God had other plans. As a kid living with HIV, I was assigned a social worker who kept me involved in lots of events for children battling different life-threatening diseases. I attended camp every summer, which gave me the chance to be around other kids who understood what I was going through. We all had our camp “crushes.” But I would soon find out that dating at camp was a lot different from dating in the real world, and that the dating and hook-up guidelines we follow as a society are not inclusive of someone living with HIV – someone like me. My parents are old-school, African-American, super-religious types, so I never had the sex talk. My social worker at the hospital didn’t say this to me directly, but in her attempt to educate me on HIV transmission, without realizing it, she led me to believe that I would never be able to have sex or have babies. And there was one huge thing she forgot to prepare me for: stigma.

The next time I learned about HIV, I was a seventh-grader in Sex Ed. It terrified me. I remember sitting in a classroom of about 30 kids, with the health educator showing us all these disgusting pictures of sexually transmitted diseases, and listening to how grossed out everybody was. When she started talking about my experience, I got really quiet. The pictures she showed didn’t look anything like me. Instead, they were pictures of middle-aged, white, gay men or Africans wasting away. They were all pictures of people who were really sick or dying; there were no pictures of people who were healthy and living. Everyone left class believing that if you have sex, you could get HIV. And that if you get HIV, you are going to die. It made me even more afraid to have sex, and it further deepened the notion in my mind that someone with HIV wouldn’t be able to have a normal, healthy sex life.

Throughout the years, I had to learn how to navigate dating and sex with HIV on my own. The only thing I ever learned about disclosure was from my mom, who told me to be careful who I shared my business with because people in this world could be cruel.

Although my mother didn’t mean to, her advice, along with the isolation I was already feeling, further perpetuated stigma. She made me feel like I had something to hide, which in turn created more feelings of fear and shame. I struggled the hardest with stigma in my adolescent years. When I was younger and trying to fit in with the rest of society, it was hard for me to accept my HIV status, because it came with so many different misconceptions.

Dating and maintaining a social life became difficult for me, because of all the ignorance surrounding my experience. I dealt with many fake friends and lovers who would gossip about me and disclose my status to people, with the intent of making me look less attractive. I started to internalize all of the negative things that were being said.

I never thought I’d be able to have kids; I didn’t know what I could do sexually; I didn’t think I would be able to find someone open-minded enough to want to date me. I watched my mom pass away from AIDS-related illnesses during my junior year of high school, so I never really planned for a future, because I didn’t think I’d live to be the age I am today (33 years strong). I went through this really dark stage in my early 20s, and I almost died from rebelling and not adhering to my medication.

Stigma is killing people more than the actual disease now. Treatment adherence is greatly affected by the stigma. The treatment has come such a long way, and people are able to live long and healthy lives with HIV – if they can get connected to care and stay adherent to HIV medication. It is no longer a death sentence. It is a chronic, manageable illness.

I see it happen often. When someone is newly diagnosed, they internalize that stigma, which can lead to deep depression. They believe their lives are over and they will never be able to lead a normal, healthy life or find love. In my opinion, it’s because they struggle with this sort of pre- and post-diagnosis identity crisis, and being positive becomes hard to accept. I don’t have a pre-diagnosis identity to refer to, but I do know what it’s like to internalize the stigma that has been programmed into our minds.

The stigma has never sat well with me. Living with HIV is my normal, and I didn’t die. I am still thriving. I had to grow to understand that the insults, judgments, and shade that people attempted to throw were actually projections of their own fear, misconceptions, pain, and insecurities and that it had absolutely nothing to do with me.

For so long, I just let people gossip about their perceptions of my reality. Even today, every time I get up and share my story, I am extremely nervous, and my anxiety starts to kick in. I think it’s because I am experiencing PTSD from all of the stuff that I went through growing up, and remembering all the things people said about me. But then, as I push through that fear, I experience this sort of liberating sensation. I get to portray my experience in the way that I want to, and I get to change the narrative.

In hindsight, I can’t believe I let stigma keep me silent for so long. Now that I have embarked on this advocacy journey, it is like I am seeing things through a new lens. I have discovered this new world full of people who can either relate to living with HIV or with other parts of my story. By remaining silent, I was unconsciously allowing that stigma to thrive in the silence.

Disclosure has been one of the scariest, most difficult things to deal with in my experience. Yes, I have encountered a lot of ignorance and hate, but I have also found a lot of people who understand me, like me, and love me regardless. Contrary to what people believe about my experience, it has been a blessing in disguise, and I know now that this is a gift. I believe God created me specifically for this purpose: to change people’s perspective on what it means to live with HIV. To know me is to love me, and the beauty in that lies in the fact that my whole being dispels the stigma.

I am a Beautiful Black Queen, and my status doesn’t change that.